Funerals are a cultural event. As funeral directors, we are sometimes asked to understand diverse customs and rites that are not our own. How you react when asked to open up your funeral home to another culture and their traditions is important to the future of your business.

Earlier this year I had the honor of serving the Yang family when their father passed away. The Yangs are Hmong, an ethnic group of Southeast Asian decent located predominately in Southern China, Vietnam, and Laos. The Hmong people were broadly depicted in the 2008 Clint Eastwood movie: “Gran Torino.”

Mr. Yang was born in Laos and fought with the Royal Lao Army alongside the U.S. Military during the Vietnam War. This was often referred to as the “Secret War” because of America’s covert involvement in the border conflict between Laos and the North Vietnamese.

Mr. Yang assisted the United States Military at great personal risk and when the U.S. subsequently withdrew their troops from the region, his family was exiled from their home. They found refuge in Texas where they formed a tight-knit family community. The Yangs do not identify themselves as Laotian. They are proud Hmong.

♦♦♦

When the Yang family first called on our funeral home, they were very upfront about their needs and wants. They had three concerns: Time, Space, and Food.

Time: Hmong funeral tradition consists of several full days of services culminating traditionally with a burial on the final day. We found a clear weekend with no other services scheduled so we could designate a Saturday, Sunday, and Monday for their family’s exclusive use of our entire funeral home. That is an ingredient of concern number two…

Space: We are not a large location by some standards, but we have some space to work with. Our chapel can seat 185, and we have two state rooms as well as a small reception room. All of our space would be needed to welcome their family but our reception room was the key. It was just large enough to hold the food. Not the guests eating it, just…

…the Food: When I tell you that food is a big part of Hmong funeral tradition, you better believe I mean BIG! We used six of our folding tables and six of our cocktail tables just to hold the serving dishes. We didn’t need to supply any of the food. We just needed to accommodate it.

Food, Food, FOOD!

To accurately describe the amount of food served and eaten inside the funeral home over those several days would be impossible. A small army of family and friends cooked three daily meals at the family’s home and brought each meal over to be eaten hot and fresh: breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

No leftovers. No store bought sandwich trays… truly authentic Hmong cuisine.

The line for each meal stretched down our back hallway to the front foyer.

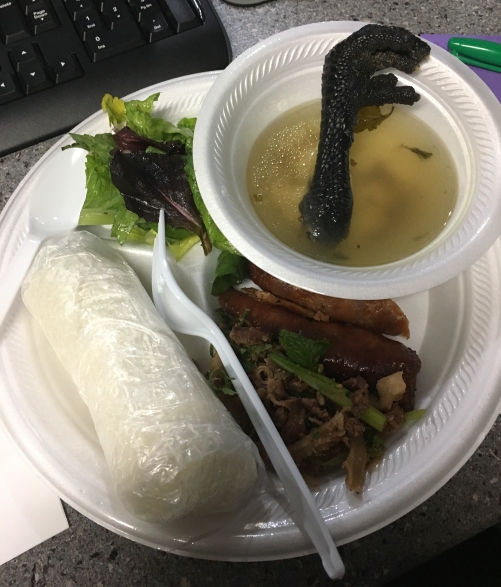

Freshly slaughtered beef in spicy sauce with bamboo shoots, sticky rice, beef tendon broth, desserts galore such as neon green and pink sticky breads, puddings, cakes, cookies, and a sweet coconut milk drink filled with fruits of several different textures and tastes akin to soggy cereal (in a good way)… and that was just one of the lunches.

Dinner tended to be much more rustic. One night was a chicken soup in which I had a boiled chicken claw hanging out of my bowl. A tangy beef dish with more bamboo shoots and sticky rice, as well as a leafy green salad. Lots of broiled and steamed fish, some of which were wrapped in banana leaves.

The claw may not look appetizing to some, but the broth was fantastic.

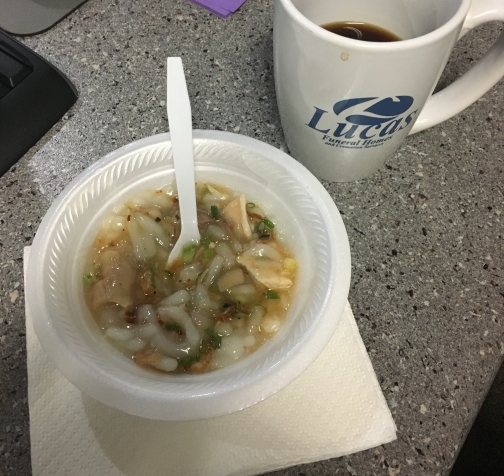

Breakfast usually began with a giant crock of chicken porridge that was akin to chicken and dumplings. I dressed mine with green onions, fish sauce, and a dash of homemade chili oil… “Not too much!” they’d say, as I attempted to draw a large spoonful from the jar. I’m glad I listened. It was tasty but extremely potent.

Chicken porridge with spicy chili sauce.

In order to serve and consume all of this food, we definitely needed space.

Space for activities…

Out of necessity, we converted the stateroom adjacent to our reception room into a dining hall. The family rented twenty additional folding tables and one hundred and fifty chairs to be able to seat their family and guests. A few days before the service, the son came in and thoroughly measured and mapped the space in the stateroom to make sure we could fit as many tables in as possible.

The rental company dropped off and the family helped set up the tables and chairs.

Family and friends enjoying a hot meal in our stateroom.

We had additional tables that ended up under our portico because it decided to storm that weekend and our uncovered patio was no longer unusable as overflow.

Our chapel setup was routine. The casket remained open and surrounded by flowers and photos. Tradition dictated that the family choose an all wood casket. It is believed by some Hmong that metal cannot be buried with the deceased or else it can draw a curse on the family. A shroud or “spirit shield” is often employed to keep a family’s enemies from secretly placing metal objects in the casket.

Our second stateroom was used as an area for guests to donate to the family. A desk, chairs, and a little privacy was all that was needed to perform this customary act of respect.

What time is it..?

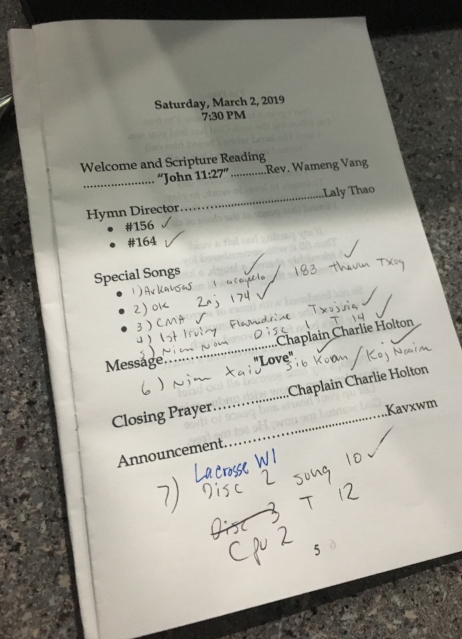

Saturday and Sunday were busy from 8 am to 10 pm. Three services each day that were usually followed or preceded by a full meal. The services were packed with Karaoke style songs sung over backing tracks that each singer would bring to me on CD’s or flash drives just minutes before they were set to perform. In the family printed memorial programs they called this portion of the service: “Special Songs”.

Each service typically had between four and five of these songs as well as a host of speakers including their minister. They were a Christian family, however a Hmong Baptist service takes on a cultural distinction that is much different than the Baptist services I had grown accustomed to.

Each service had a section for “Special Songs” but the order and amount was not predetermined.

By the end of the weekend, I was exhausted. I was lead director/sound guy for all of the services which usually lasted right up until 10:00 pm each evening. The family also invited our entire staff to dine with them at each meal, so there was not a lot of down-time.

In total, I estimate that we played about 30 different songs and oversaw about 15 hours of ceremony including the funeral services on Monday morning. By noon we had processed to the cemetery and were watching the casket being lowered into the grave after a brief committal. The time for rituals had come and gone. Everyone said goodbye.

The Yang family became near and dear to me after many days of planning, organizing, and hosting their father’s funeral. Had I said NO to their needs when they first called on me as a funeral provider, I may never have earned the tremendous appreciation for their culture I now have.

While Hmong funeral traditions share similarities to other funeral customs, as a funeral director you will need three distinct things to successfully serve a Hmong family: the time to honor their heritage, the space to make them comfortable, and an empty stomach.

Ua tsaug.

♦♦♦

Written by: Matthew Morian, CFSP

Matt is a licensed funeral director & embalmer in the State of Texas and is a founding member of Millennial Directors. He is also a contributor to NOMIS Funeral Home & Cemetery News and The Deadbeat.